The COVID-19 pandemic has caused widespread shock at an unprecedented global scale. Much of the commentary we see, especially in the press and on social media, about the impacts and prospects for the real estate industry borders on self-proclaimed gospel telling. The issues and the responses needed are often presented in black-and-white; as binary choices. They aren’t. There are plenty of nuances, and the future remains very uncertain. So, as the reality of the economic, social and environmental fallout begins to hit, we’ve taken a look at some of the more thoughtful emerging analysis to explore longer term implications for the real estate sector.

Fallout

The immediate implications of the pandemic for the sector have been significant. The housing market hit pause, significant amounts of office and retail space were all but deserted, and many tenants began to struggle to pay rent. For those buildings still in operation, sanitation, health and safety, and leveraging technological solutions were prioritised. Government support kicked in to soften the blow, with measures ranging from financial support for businesses to placing a moratorium on evictions and waiving stamp duty.

But what next? In many countries, lockdowns have begun to open up, while in others a second wave of infection has already led to new restrictions. Even with the emergence of potential vaccines, uncertainty over their longevity and efficacy means it would seem premature to begin talking about life after COVID-19. Instead, it seems far more realistic to discuss life with COVID-19. What does it mean to live and work in the shadow of an ongoing pandemic, and the prospect of more to come in the future? To what extent are the shifts happening now likely to continue or evolve?

Future scenarios

Recovery: For the global economy overall and the property sector specifically, different scenarios show different curves for recovery in the longer term. Several predictions suggest some form of tick shape, with the initial downward trend kicked off by the start of the pandemic, followed by a long tail of recovery. It’s suggested that the pace, consistency, and overall extent of that recovery depends upon the level of containment or recurrence of the virus and the measures put in place by governments and companies regionally and globally.

Alternative scenarios: Many of the predicted scenarios tend to be based upon a broad assumption of a return to pre-COVID growth-based models and economic drivers. Others raise the possibility of alternative future shifts. These include, for example, a move towards restricted growth or constraint that prioritises human wellbeing, or shifts to alternative models such as doughnut or circular economics. Another option is a transformation to a decentralised system, with economies and societies defined by local levels of disease burden and immunity. And at the extreme end of the spectrum is the possibility that, without effective control and vaccination, there could be a more severe economic and social collapse ahead.

Below, we explore some of the common predictions for various aspects of the real estate sector, alongside speculation of where things could head should one of those alternative scenarios[1] begin to play out.

Sub-sector impacts and trends

Office: With a sudden shift to mass home working, many offices have been left with only essential staff in attendance. The home and flexible working trend looks set to continue – with Facebook, for example, predicting 50% of its staff could be working from home in the next decade. But this doesn’t mean the death of the office. Many are predicting a longer term shift to a new form of hybrid working, in which head offices are centres for collaboration, socialisation and innovation, supported by a mix of regional hub offices and home working. This in turn could drive a renaissance in suburban commercial property and the transformation of town centres into mixed use residential and leisure hubs.

Shifts in working patterns potentially mean less use for office space, which (along with unused retail space) could see increased repurposing into affordable residential assets to help meet ongoing supply vacuums. And it almost certainly means a change in how the purpose of office space is conceived in the future, with occupier choice likely to be driven by aspects such as connectivity, sanitation, seamless design and technology for handsfree interactions, and provision of key facilities onsite.

Residential: Impacts on and experience of residential assets and home working has varied significantly depending on circumstances. For example, in some places initial pauses in housing markets have already seen some recovery, including increased interest from city dwellers in suburban or rural areas. The degree to which this sticks once aspects such as fluctuating weather and social drivers kick in will be interesting to watch. Predictions tend to place residential assets in the medium resilience category, although this will depend upon ongoing tenant ability to pay, and the narrowing of current differences in pricing expectations between sellers and buyers. And overall, the ability to comfortably and effectively work from home and have access to outside space look set to be ongoing priorities for customer choice.

Retail and hospitality: Hospitality and large portions of the retail sector have been among the hardest hit. For those that survive the initial economic shock, predictions are mixed about the degree to which the hospitality sector will recover. And in light of ongoing trends towards online and local retail, physical retail is likely to need to set itself apart through innovative customer experiences and strong purpose-led branding to compete in a less favourable environment.

Supply chains: Supply chains look set to change too, with the likelihood that increased diversification and localisation of supply could help to ensure future stability.

Winners and losers. Overall, predictions tend to point towards a few subsectors that will remain resilient in the coming years. These include logistics and warehousing, digital and tech-led assets, medical and life science assets, cold storage, independent living, and affordable housing. Traditional offices and malls look set to struggle.

Increased poverty and marginalisation accelerate ghettoization of urban areas?

- Opportunity: Take proactive measures to improve inclusivity and multi-use attributes of workplaces, buildings and communities.

- Risk: Lack of action contributes to further marginalisation by creating exclusive and isolated workforces and buildings.

Community identity shifts towards data and health focus.

- Opportunity: Focus on building unique, future-proof communities, with bottom up engagement around objectives and needs.

- Risk: One-size fits all approaches to development likely to be less attractive and successful.

Some states take control of supply chains.

- Opportunity: Focus on building relationships / partnerships with relevant local and national government agencies.

- Risk: Limited control over pricing and quality.

There are shifts in living and working patterns centred around new “pod” communities (e.g. based on health status) and / or a rise in community / regional micro-economies characterised by circular economic principles.

- Opportunity: Engage in local networks to understand direction of travel and role of property sector in emerging micro-economies. Partner with innovators and start ups to enable flexible adaptation to emerging requirements.

- Risk: Lack of engagement and active listening leads to loss of investment and occupation. Inflexibility risks being too slow to move / adapt to shifting needs.

Lab and tech start-ups flourish and require state of the art premises.

- Opportunity: Pre-empt future requirements for infrastructure / sanitation etc to ensure assets are attractive to relevant innovators and start ups.

- Risk: Those not prepared Loss of investment, increase in voids.

There’s a collapse in the real estate market / investment.

- Opportunity: Early investment in alternatives.

- Risk: Lack of preparation leads to financial collapse.

Financing and investment

With unemployment likely to skyrocket, there’s currently a rush for governments to agree and implement rescue plans that will lessen the blow and prevent a 1930s-style crash.

Interest rates are likely to remain low for the foreseeable future. An ongoing focus on efficiency, continuity, COVID-19 governance, and the ability to generate cash is likely to impact all aspects of the real estate cycle. And location criteria could well be revisited in light of shifting use patterns – with closer physical connections and relationships between different property functions and types.

We might expect to see lending criteria adjusted with increased margins to compensate for increased risk, and increases in certain types of transactions such as sale and leaseback. And the door may open wider for creative financing, refinancing, and alternative finance providers to increase market share.

Renegotiation is likely to be a watchword – from rent payments, flexible leases and management fees, to valuations of new developments and existing stock, and supplier contracts.

Across the sector, data will be key. The ability to monitor and understand everything about real estate investments – from building efficiency and usage to tenant needs and real time local or global trends – is likely to contribute to resilience and profitability for those ahead of the curve. Most of these facets are covered individually by comprehensive solutions, but no one has yet cracked the market by bringing together the full array of decision-critical property data into one holistic platform.

Although real estate may remain a compelling asset class for investors, we can expect more questions to be asked around financial models and assumptions, as well as a preference for those asset types generally considered to be more resilient for the medium and long term.

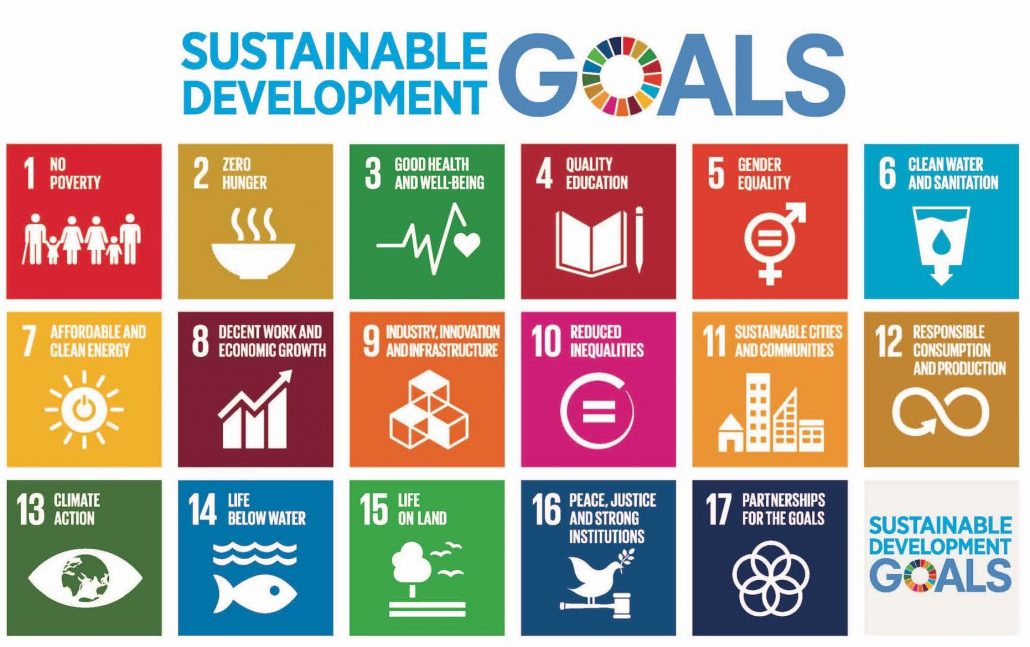

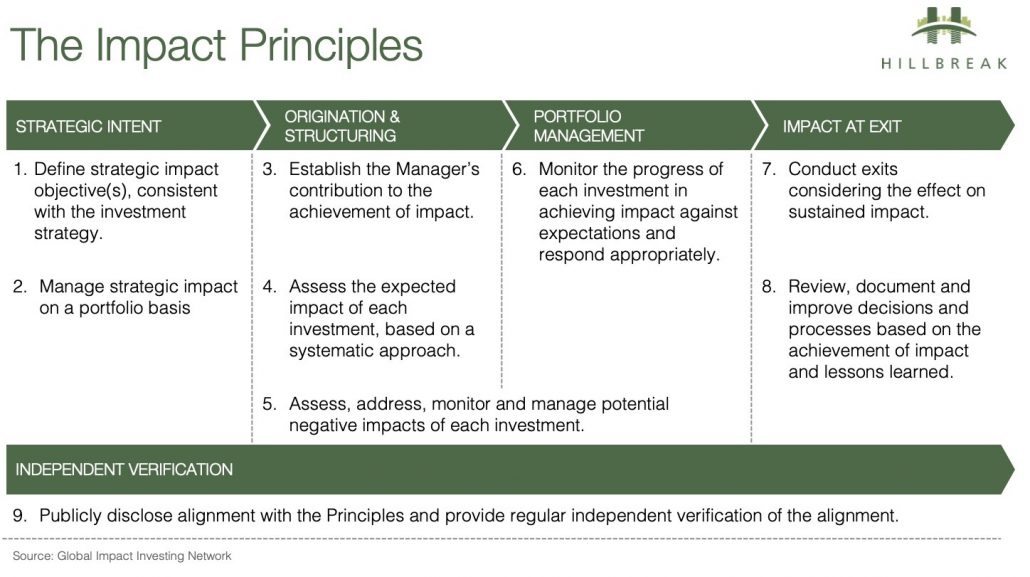

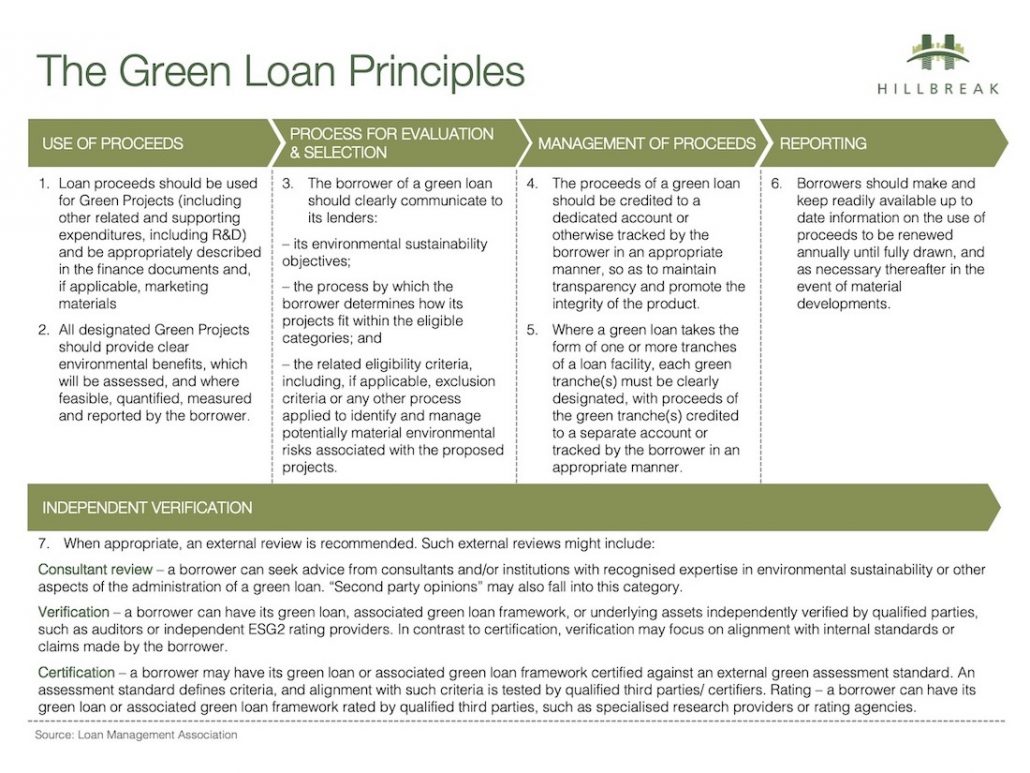

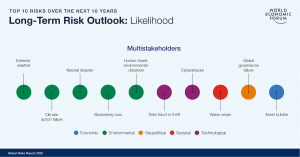

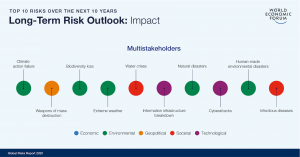

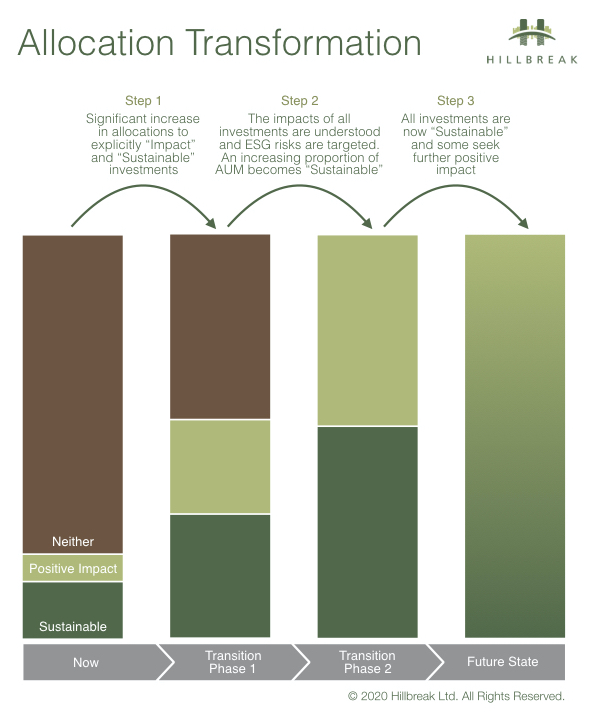

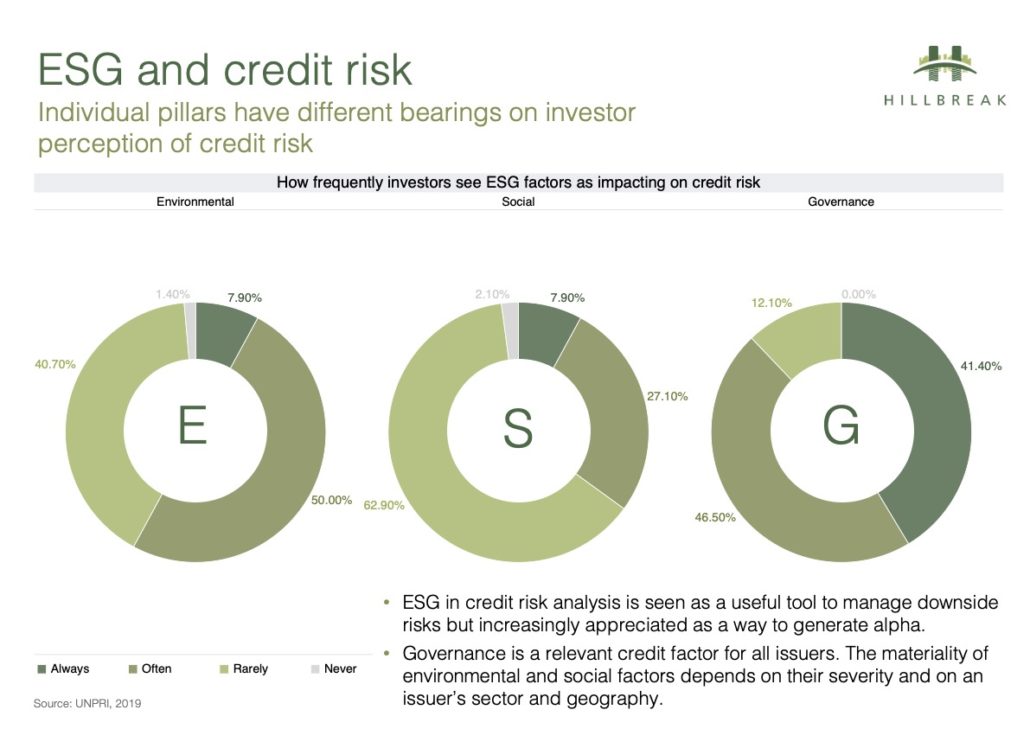

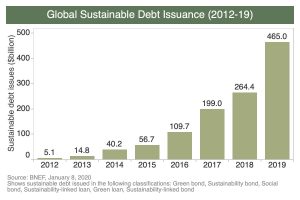

There also appears to be a common perspective that environment, social and governance (ESG) factors will continue to gain increasing attention from investors, with some predicting an increasing blurring of lines between traditional and ESG-focused investment and a further shift towards impact investment styles.

There’s a trend toward public / private partnerships and investment in infrastructure with wellbeing / community-focused objectives.

- Opportunity: Develop exemplar projects to build experience and reputation as a trusted partner.

- Risk: More complex procurement / supply / development processes with additional delivery requirements.

Governments provide public funding for basic assets and services.

- Opportunity: Focus on value added to increase competitiveness.

- Risk: Limited control over price and quality of certain services and products.

Investor focus shifts significantly in one direction (e.g. ESG; safety, security and safe bets; health and tech)

- Opportunity: Those who prepare for specific questions / requirements from investors get ahead of the curve.

- Risk: Loss of businesses, increase in voids.

Building design, utilisation and management

Space allocation: We’ve already seen major shifts in space allocation across existing assets, with the sudden reversal of the densification trend in offices, and new requirements for home working.

Ongoing lower density occupation might be matched to some degree by lower headcount across offices, retail, and food and beverage assets. The need to balance feeling safe with feeling connected for those occupying and visiting buildings is likely to require ongoing monitoring and flexible footprint management – including the rebalancing of private and communal spaces in residential and commercial buildings.

Rating schemes: Building rating schemes such as BREEAM, Fitwel, LEED and WELL are likely to continue to evolve to accommodate new trends as a result of COVID-19. And we might also see increased occupier attention to specific aspects of these schemes such as health and wellbeing – the most recent Leesman Index shows a marginal increase in overall satisfaction across Well and Fitwel certified workplaces compared with those not certified.

Design aspects: For new developments and refits, key considerations around aspects such as access and facilities, occupier density, sanitation, technology, collaboration and connectivity are likely to play a central role in design. Internal features such as communal areas, waiting areas, pop-ups, food and beverage establishments, shops and concessions will need to account for any continuation of social distancing measures.

A reduction in common-use items and contact areas (e.g. cupboard doors) is likely to be welcomed by occupiers. And with many feeling safer to cycle, drive or walk rather than take public transport, space and facilities will also need to accommodate changing travel preferences.

The journey into and through any building is likely to look and feel quite different from now on. For example, in a typical office, automatic doors might lead to a low or no-desk reception protected by screens, with automated or e-badge delivery and sanitation stations. Accessible stairwells and well-managed, low occupancy lifts will be essential features.

For retail and food & beverage assets, sanitation and registration points, one way systems and tech-assisted, low-contact experiences could become the norm.

Green construction: We are likely to also see an acceleration in the drive for greener construction, in the context of a growing number of zero carbon commitments and ever-increasing calls to #buildbackbetter in the wake of the pandemic. Many are seeing this as an opportunity to reset and rethink, although the extent to which this plays out in practice remains to be seen.

New systems: To reduce the risks of infection, ventilation and humidity controls may need upgrading, and will need careful monitoring and management across the board. Meticulous, conspicuous cleaning and sanitation regimes have already been widely introduced and look set to remain essential – both to reassure tenants and visitors, and to limit virus transmission.

Any new policies and protocols will have to take account of evolving expectations for social and physical distancing, working from home, cybersecurity, flexible working and flexible people, transport – alongside wellbeing, safety and hygiene.

Clear, visible communications and signposting will be key in supporting visitors and occupiers to understand what measures are in place within a specific building, and to be clear about what’s expected of them. Training and education programmes for tenants and onsite staff are also likely to play an important role in ensuring good COVID governance and bolstering confidence.

With the full extent of the physical and mental health impacts of the pandemic still unknown, easily accessible support services will be essential across all asset types.

There’s an increase in zero hour contract / no contract workers for low paid workers (e.g. cleaners / FM).

- Opportunity: Displaying leadership by ensuring good working conditions, employment security and fair living wages for suppliers and contractors.

- Risk: Lack of action leads to widening inequalities and an unmotivated, high turnover, staff base.

Regular testing is required for all employees and occupants and / or civil and political unrest increase use of private security firms and require more advanced security infrastructure within and around buildings.

- Opportunity: Prepare assets for increased health / testing requirements and potentially increased surveillance / security requirements. Develop in-house expertise.

- Risk: Increased costs from use of external agencies. Lack of preparation leaves some assets unfit for occupation / at risk of health or security breaches.

Increased on-street and in-building security (checks and surveillance) become the norm, alongside immunity IDs determining who can and cannot enter buildings and spaces.

- Opportunity: Development of health surveillance-ready buildings and guidance.

- Risk: Increased inequality among employees and occupiers – risk of exclusion based on health status and potentially other factors (e.g. if immunity IDs are easier to access for certain groups).

Innovation and tech

New applications: The rapid utilisation of technological solutions has facilitated changing working patterns during the pandemic. It’s also enabled the reopening of several sectors through remote property viewings, at-table ordering, and a range of other hands-free, no-contact applications.

It’s no surprise that tech and data look set to play an ever increasing role in the aftermath. Wearable tech and apps within buildings could become the norm – providing reminders to use hand sanitiser or clean desks, monitoring face touching, giving updates on health and security statuses, and providing information on who else is in the building. Shopping, ordering and registration apps could remain commonplace in pubs, restaurants and retail establishments.

The visibility and usability of this type of tech is likely to be central to the rebuilding trust between occupiers and landlords, with tenant experience platforms already playing an important role in understanding behaviours, concerns and needs.

Smart systems: Data-led, smart solutions should enable building managers to track occupancy, and generate insights about local health and economic scenarios and the needs of individual tenants. And depending on how the pandemic plays out, we might see a long-term shift to ongoing employee, visitor and occupier health screening.

Up-to-date digital and analytical capability is likely to be important for tenant attraction, commercial lease negotiations, asset valuation, and operational efficiency. Tech is also likely to continue playing a key role in collaboration, as well as enhancing occupier experience through telehealth, on-demand concierge, digital leasing processes, and the formation of digital communities.

Privacy: All of this has implications for data protection and privacy – an aspect that perhaps gets less attention in the midst of a health emergency, but which is likely to rise up public consciousness as the implications of a significant increase in points of contact with new apps and private companies becomes apparent. Careful data handling and privacy controls should remain central to any new digital systems.

Building and company health statuses are required and reported, defined by real-time data and testing.

- Opportunity: Prepare for increased health data requirements and reporting lines.

- Risk: Lack of preparation leaves some assets unfit or undesirable for occupation / at risk of health breaches. Potential customer push-back if health / privacy balance isn’t right.

Balancing priorities for a sustainable recovery

Calls for a sustainable recovery are on the increase, for example the open letter from more than 200 leading businesses – including Hillbreak – to the UK Prime Minister urging the delivery of a clean, inclusive and resilient recovery plan. Many in the public and private sectors are committing to putting aspects such as wellbeing and climate at the heart of recovery plans. This is heartening, but in reality will require a keen focus on balancing priorities and – crucially – understanding the data.

Already, the environmental implications are complex. On the one hand we’ve seen an increase in the use of disposable, single use items as hygiene has taken priority – requiring a longer-term rethink of in-building waste facilities and recycling streams. And increased ventilation and maintenance regimes alongside extended operating periods are likely to increase energy use and carbon emissions. But on the flip side, a reduction in travel, a renewed focus on sustainable building design, digitisation, and shorter supply chains should contribute to a decrease in emissions.

As recovery plans kick in, data collection and analysis tools will be essential to understanding the range of causes and ultimate effects on energy and water use, waste and emissions.

This extends to understanding the needs and drivers of individuals and communities. For example, there is evidence of growing consumer preference for story or purpose-led brands with strong sustainability credentials, and of a desire from some for wellbeing to be prioritised above economics. But in reality, how this balances with concerns about hygiene, sanitation, cost-cutting and convenience is uncertain.

With ongoing uncertainty, dialogue with employees, occupiers, investors, and other key stakeholders will be essential in understanding evolving needs and concerns. A much closer partnership between landlord, occupiers and managers could become the norm from now on, with a shared focus on safety and in-building experience. Trust, value and responsiveness are likely to be essential factors in future occupancy choices, with good engagement playing a vital role in all three.

The pandemic has caused global shock, but also offers an opportunity to rethink organisational resilience, sustainability and wellbeing. Much of the way forward will depend upon the ability to control the virus through testing, treatment and potential vaccines, alongside the fiscal, social, and environmental measures put in place across different regions. And any number of new unexpected global events could change things all together. Leading companies might be wise to engage with sociologists, futurists and tech experts, to gain insights into likely scenarios and be prepared for a range of possible futures.

Read more about Hillbreak’s strategic foresight resources.

Circular economy / doughnut economics lead many public and private sector strategies.

- Opportunity: Develop exemplar projects and data collection to prepare for increased focus on circularity and non-financial objectives.

- Risk: Those slow to prepare for circular / non-financial focus will get left behind.

Society and governments placed increased attention on community and diversity (including social diversity, diversity of production, etc).

- Opportunity: Focus on building unique communities, with bottom up engagement around objectives and needs.

- Risk: One-size fits all approaches to development likely to be less attractive.

The preference for companies with purpose sticks.

- Opportunity: Companies with strong ESG focus and mission / purpose will perform better.

- Risk: Battle for niche / positioning dilutes impact.

Strict border controls limit immigration and potential for economic migration for work

- Opportunity: Investment in upskilling and education for local workforces.

- Risk: Lack of essential skills and experience. Limits on within-company moves (e.g. to new jobs / regions).

The desire to volunteer sticks and becomes central to personal identity.

- Opportunity: Implement business-relevant volunteering programmes / support, flexible to local need and interests.

- Risk: Volunteers from the sector volunteering outside the sector may begin to fill voids left by high unemployment, risking burn-out and reduced workforce capacity. Volunteers working within the sector require ongoing investment to ensure appropriate skills and knowledge.

Social and environmental conditions are attached to new developments.

- Opportunity: Assets with high social and environmental performance will perform better.

- Risk: Those unprepared for higher social and environmental standards will lose out.

There are restrictions placed on growth / new developments.

- Opportunity: Focus on upgrading existing assets to meet ESG and futureproof expectations.

- Risk: Loss of skills/experience within the sector.

Main sources

[1] Doughnut economics is based on the concept of fulfilling the basic needs of everyone on the planet within the environmental limits of the planet – with the doughnut offering a “safe operating space for humanity”. It is build on the idea of regenerative, distributive and collaborative economies, where success is measured by measures other than growth – e.g. equity, wellbeing, and innovation. A circular economy is one that keeps resources in use for as long as possible, through recovery, reuse, recycling, repurposing and regeneration, thus minimising waste.

The amount of

The amount of