IMPACT FINANCE SERIES: Part I – The Jargon

Series overview

In this series of articles we explore the sustainable, responsible and impact investment landscape.

- Beginning with “Part I – The Jargon” we attempt to break down the language barrier and explain what is meant by terms like “Impact”, “Green”, “Sustainable” and “Responsible” when it comes to investing.

- In “Part II – The Markets” we explore how the various parts of the capital markets isolate, prioritise and manage specific climate and social risks, and how their risks and investments are interrelated through equity, debt and insurance.

- “Part III – The Assets” explores how the real estate market is using and driving sustainable finance markets, as well as the financial risks of falling behind.

- “Part IV – The Future” builds on these topics to consider how the sustainable investment market might create winners and losers, drive new financial products and dramatically improve our management of risk.

So, beginning with Part I – The Jargon:

What counts as Sustainable / Responsible / Impact Investment?

I have advised on “impact investing” since 2009. The global financial crisis had created an opportunity. For me personally, it meant working with the UK government to advise on business finance markets, and specifically how to use them, and change them, to speed the economic recovery and thereby limit the social implications of the crisis. This included acting in a lead advisory capacity on the establishment of the £3bn Green Investment Bank, the £1bn British Business Bank, and the £200m London Green Fund.

Since then, I have worked with lots of investors and intermediaries seeking to make an impact while they make a financial return. I have also seen others accused of “green-washing”, or more recently “SDG-washing”, a term applied to those who seek superficial alignment to the UN Sustainable Development Goals in their marketing collateral and disclosures. So, how can an investor or shareholder make informed allocation decisions and know what impact they are really having?

Looking back to the early days of my career, one of my key indicators as to whether an organisation was serious about impact investment was whether my meetings included the client CFO or CIO. If not, it was unlikely that much would be done about any good intentions we might explore. Increasingly – almost invariably – meetings now involve CEOs, CFOs, CIOs, or the whole board. Business leaders and their shareholders are getting passionate about social and environmental risks and opportunities. CFOs and CIOs are getting clearer evidence of the potential costs that social and environmental risks pose for their bottom line. As a result, ESG and responsible investment teams are under increasing pressure to advise on these risks and help their organisation, and their clients, to capitalise on the opportunities.

Without doubt, the jargon is myriad and confusing. Every-day words are now being used by ESG specialists to mean very specific things, which might not be immediately obvious to others. The lexicon is growing and changing, as is the related regulatory framework, especially in Europe. A few of the key investment styles and themes to master, and which we characterise below, include:

| Investment Style | Investment Theme |

|

|

These terms are not mutually exclusive, and the overlap may be less than you think.

Investment Styles

Sustainable

The EU has helpfully been setting about formalising the way we use these terms with respect to financial disclosures and investments[1]. For the EU, ‘sustainable investment’ must:

- contribute to environmental objectives in a measurable way, or

- contribute to social objectives, and

- do no significant harm to any social or environmental objectives, and

- follow good governance practices.

This is significant as it ties all three Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) pillars into the concept of sustainability. It also borrows the concept of non nocere, meaning “do no harm”, from the hippocratic oath familiar to medics around the world.

Under new EU rules, a product cannot be marketed as environmentally or socially sustainable based on just one or two factors. It must effectively be neutral or positive on all other environmental and social factors, and “good” from a governance perspective, in particular with respect to sound management structures, employee relations, remuneration of staff, and tax compliance.

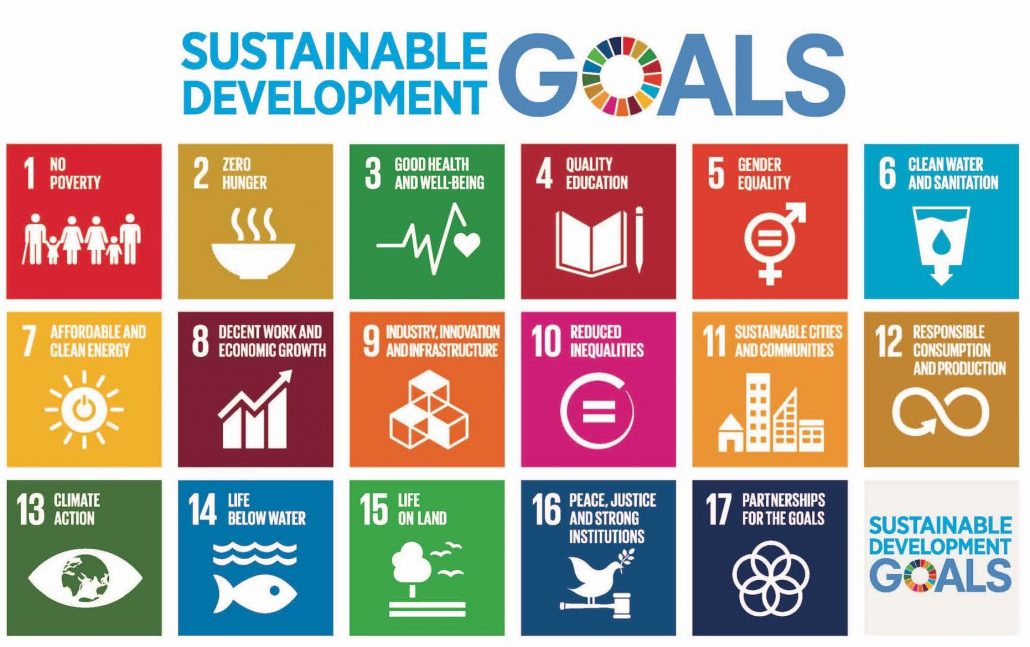

Back in 2015, the UN launched the increasingly familiar Sustainable Development Goals[2], an expansion and development of the former Millennium Development Goals. Significantly, whilst developed for the principal purpose of directing and aligning intragovernmental policy and programmes towards global societal challenges, they have found significant appeal amongst the investment community, effectively acting as an off-the-shelf taxonomy. In this sense, they highlight a number of ESG themes and factors as being inherent to the “sustainable” investment label. These goals aren’t worded identically to the EU’s objectives and examples, but they do align.

UN SDGs

Responsible

The UN Principles for Responsible Investment[3] outline how ESG factors should be part of investment decisions and active ownership. Driven by investors, this again seeks not to duplicate the work of others in defining the ESG issues, but instead defines how the issues should be treated by investors and intermediaries, in terms of both investment process and related corporate behaviours:

| Summary Principles | Translation |

| Incorporate ESG issues into investment analysis and decision-making processes | Put your money where your mouth is |

| Be active owners and incorporate ESG issues into ownership policies and practices | Do it across your business, not just in a few token investments |

| Seek appropriate disclosure on ESG issues from the recipients of capital | Hold the organisations you fund to account |

| Promote the Principles within the investment industry | Get other investors and intermediaries on the same page |

| Work together to enhance our effectiveness in implementing the Principles | Apply some collective pressure and share best practice |

| Report on our activities and progress towards implementing the Principles | Keep each other honest |

It is quite commonly understood that responsible investment therefore relates to the integration of material ESG factors into investment processes and decision-making, such that harm is avoided and ESG risks are mitigated. At the heart of the UN PRI is the pursuit and delivery of competitive, risk adjusted returns, recognising that material ESG factors that are not considered and managed effectively will likely result in weaker financial performance. The market evidence to support this theory now borders the irrefutable. The inherent bond between responsible investing and fiduciary duty is, as a result, understood by the vast majority of informed investment professionals.

Impact

According to the Global Impact Investing Network[4], impact investments are made with the intention of generating positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return.

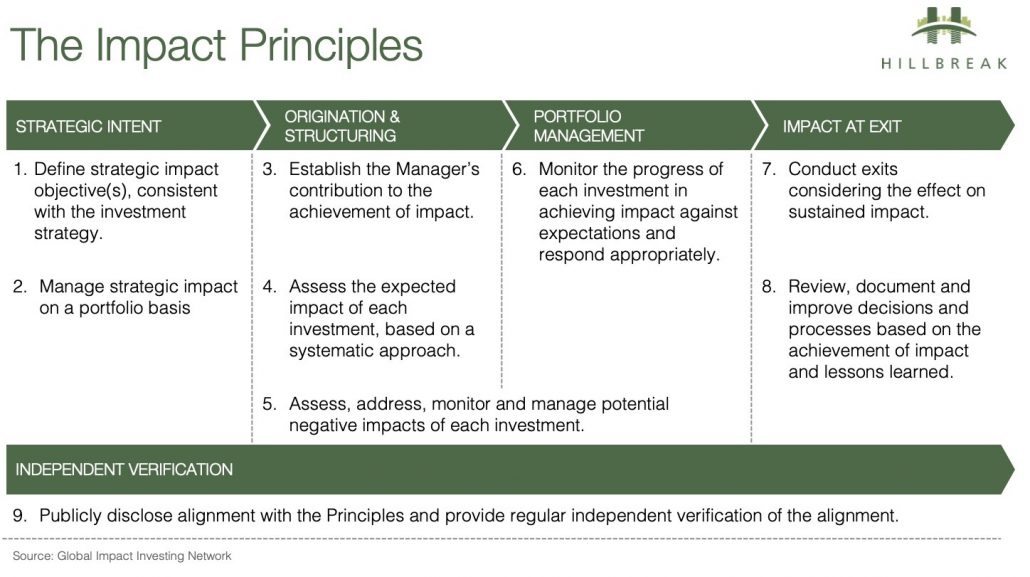

The IFC has augmented this by developing a set of impact investing principles[5] backed by 60 public and private investors to define how this should be done in practice. This adds specificity about the requirement for measurement, management, verification and reporting of impact. This is clearly about more than just passively taking assets which are “good enough” or making minor improvements. It denotes a more active, intentional and additive approach to investing risk capital to mitigate environmental and social risk and deliver positive outcomes.

The Impact Principles

Notably, these principles don’t include the “do no harm” requirement of the EU, or the comprehensive industry engagement and investor reporting requirements of the UNPRI. Nor are they specific about whether only the intended positive impact or also the potential negative impacts should be measured and reported.

The Impact Management Project[6], which includes the GIIN, IFC and PRI has gone further to clarify that impact management should be “the ongoing practice of measuring and improving our impacts, so that we can reduce the negative and increase the positive”. Investors should therefore expect to see measurement of the good and the bad, and judge the performance of their investments (and their intermediaries) on this basis.

Transition

Related to ‘impact’ investing is the term ‘transition’, typically used in the debt markets as labelling for ‘transition finance’. This has come into use as a descriptor for investments seeking to enable improvements in the climate and energy performance of assets and businesses. The climate transition is usually referenced to specific targets to reduce GHG emissions and limit the expected global temperature increase to 1.5 or 2 degrees. The targets to which these investments align are not necessarily consistent. Often, they align to the targets set out in the Paris Agreement and reiterated by national governments. However, increasingly, local authorities and businesses are setting their own, more ambitious targets, either increasing their level of ambition in terms of quantity or timing of emissions reduction. Similarly, the energy transition is commonly understood to mean a transition away from fossil fuels (or to cleaning them up, such as through carbon capture and storage) and towards renewable and sustainable energy sources. In the space of transition finance there is, therefore, no standard benchmark or level to which the investments must perform from an ESG perspective. They must simply seek to make a contribution.

‘Transition’ is also used in the context of a ‘just transition’. This concept has been developed by the UN Sustainable Development group[7] and links the climate and energy transition to the societal goals set out in the SDGs. Under this model the climate transition must not be achieved at the expense of social progress and should actively seek to contribute to the societal goals.

Investment Themes

Environmental

The EU’s approach to environment – set out in its draft regulation for the establishment of a framework, or ‘EU taxonomy’ to facilitate sustainable investment – is as one might expect. It defines six objectives and cites several issues as examples of factors one might consider:

| Objectives [8] | Examples [9] [10] |

|

|

One could be forgiven for thinking, therefore, that environmentally sustainable investments simply need to contribute to one or more of the environmental objectives, be neutral socially, and be well governed. Not quite! Controversially, the EU goes further. As well as citing specific standards and guidelines from the OECD and UN[11] which must be met with regard to social and governance issues, it requires that the investment “complies with technical screening criteria” on the environmental side.

The technical criteria established for environmental sustainability have been criticised for a couple of key reasons. Firstly, the regulations use existing technical measurements and standards to define what will meet the threshold for products and activities to be labelled as environmentally sustainable. This is fairly easy mud to throw. In a complex space where no one size fits all, most specialists can see significant scope for improvements in the global benchmarks (such as GRESB[12]) and EU regulations on Energy Performance Certificates for buildings[13]). Of course, these regulations and standards are not perfect, but they are established tools which are available now and can be improved and built upon in future. So, the structure of the EU’s approach makes sense, and leaves room for improvement as measurements and standards become more effective over time.

The second criticism is that the technical standards set too high a hurdle, including only very green (or “dark green”) investments, and excluding other activities which would contribute to the objectives, but not to the same degree. This criticism misses the point. A key objective of the legislation is to provide an easy flag for investors. The “sustainable” label in the EU seems intended to highlight those investments which are ostensibly “good enough” or “safe enough” in terms of having limited exposure to ESG risk. By definition, one would expect these investments to exclude those where the investors’ allocation of capital might be expected to have a negative impact in terms of environmental or social change. Arguably, also by definition, one would expect these investments to exclude the majority of existing investments, including those intended to make only partial or limited improvements to the management of environmental or social risks . This label is effectively a ‘safety’ label, or a hallmark indicating high ESG quality assets for positive screening purposes, and not about ESG risk management and quality improvement across a whole portfolio.

Admittedly, the EU intention to establish ‘brown’ criteria within the taxonomy at a later date, capturing those activities that are deemed to cause significant environmental harm, would enhance the potential application of the framework within the market by bringing into play a broadly accepted negative screening threshold too.

Social

The EU has indicated that a comparable approach will be taken to defining socially sustainable investment, namely that the investment must:

- contribute to social objectives, and

- do no significant harm to any social or environmental objectives, and

- follow good governance practices.

The social objectives which have been established to date are:

- tackling inequality

- fostering social cohesion,

- improving social integration

- improving labour relations

- investing in human capital

- investing in economically or socially disadvantaged communities.

Climate

Driven by regulators, and gaining private sector support, the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) has identified a number of financial risks as being “climate-related”. Its approach fits broadly with the intuitive, everyday interpretation of the word ‘climate’ as being related to carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, and their effect on rising temperatures, sea levels, and extreme weather events. They don’t explicitly mention every single climate issue – notably scarcity of natural resources, air quality or biodiversity – but these are implicit factors which impact on the risks identified. This is not a shortcoming, rather a product of its approach: defining the financial risks (below) and opportunities, rather than duplicating work done elsewhere in defining the underlying issues. Rather sensibly, anything climate-related which exposes investors to financial risk should be considered when making climate-related financial disclosures. Therefore, those making the disclosures should have an eye on the issues and examples already outlined by the EU and UN.

Green

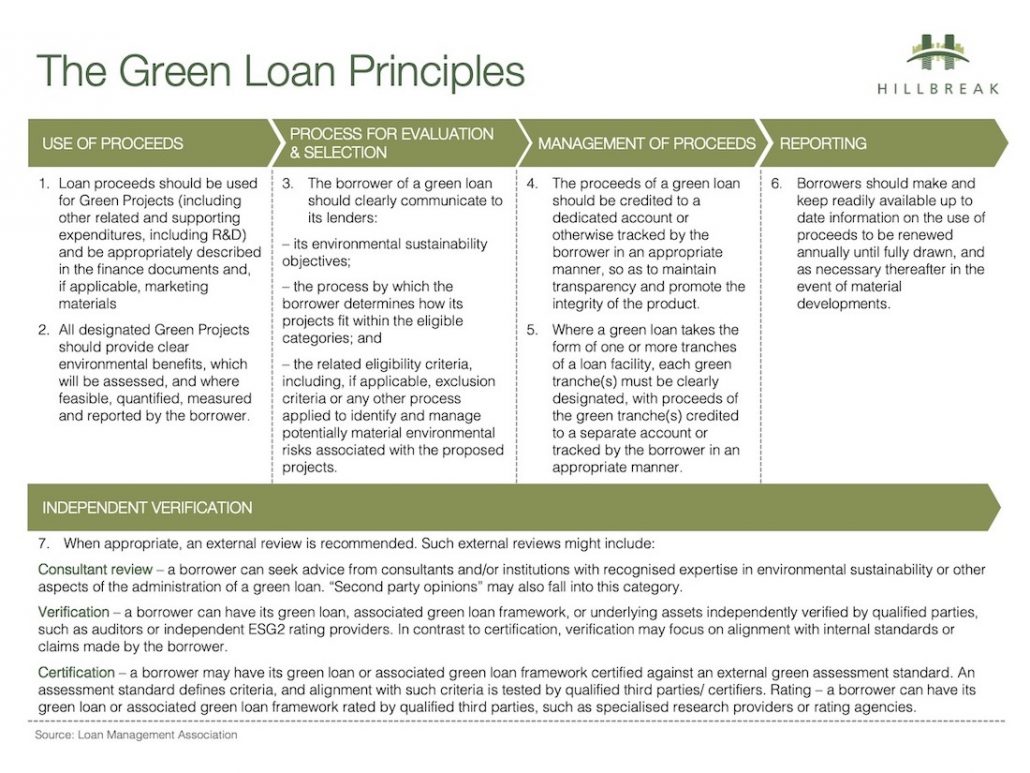

Much work has been done to set out how ‘green’ finance should be issued and managed, such as the Loan Market Association’s Green Loan Principles (below)[14] and the International Capital Market Association’s (reassuringly similar) Green Bond Principles[15].

Green Bond Loan Principles

As well as setting out the principles for how this form of finance should be done, both give examples of what might qualify as a ‘green’ use of proceeds, including such things as renewable energy, energy efficiency or ‘clean transportation’.

Surely, therefore, launching a Green Bond to finance more fuel-efficient vehicles would be green? But what if those vehicles were oil tankers, as with the Green Bond issued by Teekay Shuttle Tankers? Then, opinions differ[16] [17] – some find any investment in certain sectors, such as fossil fuels, unacceptable. Others are willing to invest to “clean them up” as part of the transition to a less carbon intensive or ‘net zero’ future. So, is it enough to make something better, even if it’s still not going to end up fully or dark ‘green’? This is where the growing distinction between sustainable investment, and impact or transition investment is helpful.

Arguably this is impact or transition financing, not sustainable financing, and the use of the term “green” is an unhelpful badge. It is a label which is controversial and has covered all manner of sins in the past, allowing companies to claim “green” credentials while doing more harm than good, or while spending more on advertising how “green” they are than they do on delivering real environmental improvements within or through their business. It evokes environmental issues without giving any real indication as to the purpose of the deployment of the capital: taking lower or higher risk, being passive or actively managed.

Investments may be sustainable and have no impact (such as buying a building which already exceeds the EU’s technical quality threshold), or be sustainable and have impact (such as investing to improve a building to meet the technical threshold), or may have impact but not reach the threshold above which investments would qualify as “sustainable” under the EU lexicon. In short, the terms sustainable and impact are not mutually exclusive, nor is one confirmation of the other. An investment may be sustainable, impactful, both or neither. A clear understanding by all actors of the distinction between sustainable and impact investment should help investors know what they’re getting, and to start to ask how much impact their money really has – both positive and negative.

The Markets

Now that the terminology is maturing, and in many cases is being formally defined in legislation, we can start to understand how these terms have been used (and misused) in the capital markets. The lexicon is useful for investors seeking to isolate, prioritise and manage specific climate and social risks, and innovative stand-alone and inter-related products have emerged in the equity, debt and insurance markets. We explore these in Article 2 in this series.

[1] REGULATION (EU) 2019/2088 on sustainability‐related disclosures in the financial services sector

[2] https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

[3] https://www.unpri.org/pri/an-introduction-to-responsible-investment/what-is-responsible-investment

[4] https://thegiin.org/impact-investing/

[5]IFC – Investing for Impact: Operating Principles for Impact Management

[6] https://impactmanagementproject.com/

[7] https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/22101ijtguidanceforinvestors23november1118_541095.pdf

[8] Revision 2 of the draft regulation on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment

[9] REGULATION (EU) 2019/2088 on sustainability‐related disclosures in the financial services sector

[10] Revision 2 of the draft regulation on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment

[11] OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, including Declaration of the International Labour Organisation on Fundamental Principles, and Rights at Work and the International Bill of Human Rights;

[13] DIRECTIVE 2002/91/EC on the energy performance of buildings

[14] https://www.lma.eu.com/application/files/9115/4452/5458/741_LM_Green_Loan_Principles_Booklet_V8.pdf

[15] https://www.icmagroup.org/green-social-and-sustainability-bonds/green-bond-principles-gbp/

[16] FT – Investors balk at Green Bond from group specialising in oil tankers

[17] FT – Bankers push back against ‘greenwashing’ criticism