Strategic Foresight Prospectus

Exploring the future imaginatively.

Exploring the future imaginatively.

Given that strategic foresight inherently has a long and broad horizon, the challenge to those concerned with taking action today to secure a better future tomorrow lies largely in forging the link between the vision ahead and the bottom-line now. This final phase of “Acting” is primarily about communication – making the conceptual more material, and getting the individual and collective ‘buy-in’ of all involved. Successful implementation also entails creating an acceptable action agenda, establishing an appropriate intelligence system and effectively institutionalising strategic thinking.

A presentation protocol for policy proposals should have been designed and agreed from the outset. So far as possible, all significant stakeholders should be engaged and key decision-makers committed. Great care has to be taken, moreover, to construct a communication plan that conforms to the culture of the organisation and confronts it on its own terms. Furthermore, it should have been tested and refined in a variety of feedback activities prior to public launch. From experience, we have found the following factors worthy of consideration:

Plans, policies and proposals alone, however perceptive they may be, do not always readily convince organisations to address change. Scepticism of the findings from strategic foresight is not uncommon, and special skills on the part of the consultant are required to shape and advance an organisation’s awareness of the need to revise, reform and renew. We have always found that the ‘scenarios’ developed earlier in the process also promote a better understanding of the organisation’s position in terms of policy implementation.

It is a common conception, to which we concur, that ‘real’ change invariably only occurs through a sense of either potential crisis or great opportunity. Many organisations and their decision-makers are difficult to disturb from their comfort zones. It is often necessary, therefore, to generate a belief that the organisation cannot continue to operate in the way that it has – either through fear of imminent failure or the missed chance of boundless success. Again, there are a few pointers toward best practice.

A common attitude towards the future is one of regret: “if only we had known earlier, then we could have……”. Constructing an action plan that has at least considered unconventional thinking will at least minimise the threat of this happening.

Any organisation large enough to have a formal planning process should also possess an ordered and customised system for developing business intelligence. One that feeds into it and is properly aligned. This intelligence system should constantly be monitoring and reporting on the external business environment. Further, it provides a common process for asking questions and formulating answers. Like a form of corporate radar, it also acts as an ‘early warning system’ to detect ‘weak signals’ flickering on the horizon that are the precursors of threats and opportunities. Commonly, it is held that there are a number of key steps to this.

Increasingly, strategic foresight is being employed in response to ‘turbulence’ in the external environment. A lack of awareness, preparedness and adaptability can easily lead to organisations failing to accommodate disruption. Setting-up a satisfactory intelligence system as part of plan implementation becomes imperative.

All too often ‘futures thinking’ and ‘strategic foresight’ are conducted by corporations on a one-off basis. It is, however, becoming progressively recognised that they need to be embedded within the organisational structure and decision-making processes of the firm or agency. Scanning for trends and issues should be part of corporate daily practice, and regular analysis to reflect on the insights thus garnered scheduled repeatedly into organisational programmes. A significant initial time investment is required to establish the framework and discipline, but, once done, the practice becomes second nature, and the mindset of the organisation invariably starts to change. Quite soon, the quality of the process and the added-value of the outcomes becomes evident. Indeed, to conclude, one is reminded of the adage coined by George Bernard Shaw: “You see things and say ‘Why?’ But I dream things that never were and I say ‘Why not?’”

Strategic planning options are the policy pathways that transport the realm of long-term, big-picture vision to the reality of the need for a set of actionable tactics to tackle present circumstances. Such planning thus provides an organisation with a roadmap showing how it can get from where it is, to where it wants to be. At Hillbreak, we aim to consolidate a client’s future policy framework into no more than five strategic planning options. We have found, moreover, that there are an array of common characteristics that distinguish and define a successful strategic planning exercise. These can usefully be summarised as follows:

Strategic thinking is primarily about finding and developing a corporate foresight capacity for an organisation, by exploring all possible organisational futures, and challenging conventional thinking so as to foster better decision making today. It requires identifying assumptions about the future that might require examination, testing and subsequent modification. Most excitingly, such a futures approach through foresight can constitute an effective platform for collaborative planning. But, within client organisations, there has to be awareness, openness and a willingness to be disturbed! Strategy emerging from the bottom-up and employing unusual and remarkable sources is often best regarded.

Several major maxims make strategic thinking more impactful:

The challenge for corporate foresight in thinking strategically, therefore, is to help organisations achieve and sustain a ‘good fit’ within their evolving policy landscape so as to be able to anticipate and respond to transformational change effectively. This is about people every bit as much as it is about process.

First, and foremost, strategic recommendations must be based on the distinctive attributes and abilities of an organisation. Foresight, of course, should always emphasise the external environment and take a longer, broader view; but the consultant must also be aware of the client organisation’s internal strengths and inherent deficiencies. Strategy, perforce, has to be developed around an organisation’s core resources and capabilities, and the need for building policy options from the inside out. Again, from experience, there are a few guidelines worthy of mention:

It is, of course, good practice to stress-test strategy as much as practicable during its formulation; fixing any major mistakes after implementation can be extremely costly.

Defining a problem, and communicating it to others, so as to prepare an effective planning solution is a familiar task to all concerned in decision-making processes. A technique favoured and followed by Hillbreak comprises the following investigative process:

In the context of strategic thinking in corporate foresight the recommendation would be framed as a positive policy option.

Conclude with contingency! In these volatile days of increasing risk and greater uncertainty, it should almost go without stating that the corporate foresight consultant must help the client prepare and rehearse contingency plans for the inevitable surprises that will occur over the longer, and even shorter, term. As Aristotle discerningly declaimed: “Probably something improbable will happen”!

The essential purpose of Strategic Foresight is to make better, and more informed decisions in the present. All organisations, however, need to ask the basic questions about their future: “Where are we going? What do we want to be? And how do we know what we want to be doing?” In achieving this, they not only need to identify all the implications of alternative futures; challenge the basic assumptions of their thinking and operation; but also “think big” about their aspirations ahead.

One of our favourite sayings at Hillbreak when conducting a Strategic Foresight Exercise and arriving at the ‘Visioning’ stage is: “Imagine ahead and plan backwards”. ‘Presencing’ is the professional term. This is the reverse of the conventional ‘trend extrapolation’ mindset of most planning practices, but we believe that creating a vision for the future is vital in helping identify long-term goals and strategies. Nevertheless, it should be recognised that a strategic vision is akin to a ‘lodestar’ in that it provides an image of the future that offers direction yet is never reached. In this way, visioning is also an iterative process, as the formulation of strategies and plans may raise issues and questions that make it wise to revise the vision and the consequent strategy over time.

A strategic vision serves organisations as a template, model, or interpretive framework for making sense of the daily puzzle; as well as providing a rallying point for focusing the organisation’s work. In tough times, moreover, it can provide reassurance that current challenges will pass and are worth navigating through. It also aligns the organisation and its stakeholders around a common purpose communicating expectations to all concerned. A great vision statement, however, does not guarantee great results. Unless everyone involved believes in the vision, and acts accordingly, it is simply words on paper.

The main advantages of creating a vision of an organisation’s preferred future is that it helps:

The following guiding principles should be considered when developing the preferred future vision during any workshop.

Somewhat prosaically perhaps, the following procedure is illustrative of how to envision a preferred future in a workshop setting:

It is worth striking a note of caution regarding the very term “vision” in the context of an organisational setting, for the word itself can conjure up notions of ‘rapture’ rather than ‘reality’! Envisioning a preferred future is far more about perceptive and aspirational foresight than organisational yearning and wish fulfilment.

It has long been recognised that visionary corporations attain extraordinary long-term performance. Successive studies have found evidence that companies striving to learn and grow through futures-oriented thinking outlast companies focused solely on economic returns. A famed example by Royal Dutch/Shell found that the average life expectancy of Fortune 500 companies was under fifty years, but many were over two hundred years old. The key difference between the short- and long-lived companies was that the former focused on financial returns while the latter concentrated on the community of people comprising the organisation, maintaining a strong sense of identity and purpose through shared vision of a preferred future in good times as well as bad.

A concluding injunction for the visioning stage of the strategic foresight process is: “Dare to be the ridiculous!” The mindset should be close to Disney’s concept of: “the willing suspension of disbelief”; emphasising the presence of mind to consider even the most ‘off-the-wall’ alternative prospects, pathways and solutions, and searching for the kernel of a useful notions within them. Build, therefore, upon wild ideas and continue to ask the ‘What If?” questions.

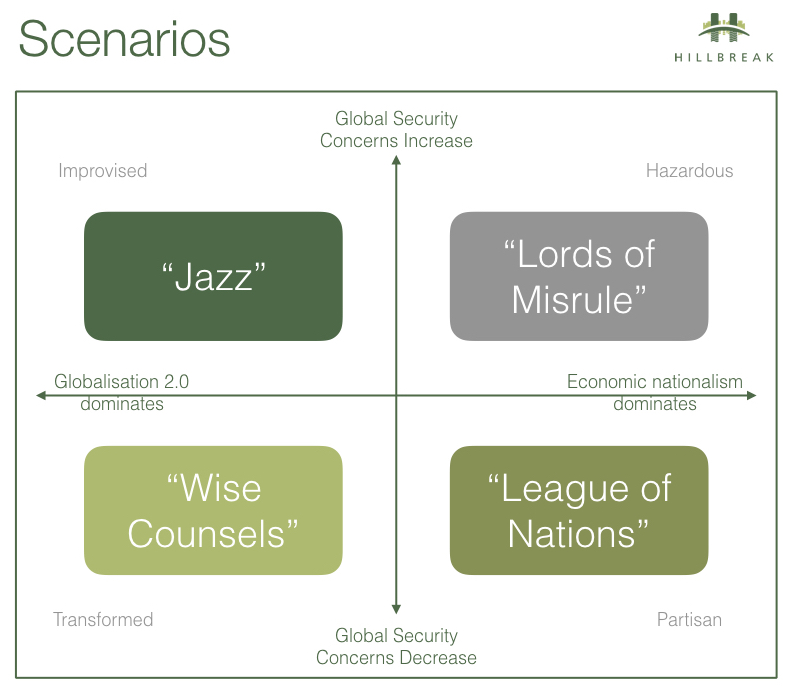

Essentially, forecasting involves generating the widest range of creative possibilities, then consolidating and prioritising the most useful for an organisation to consider and prepare for as it moves ahead. Appreciating that a key tenet of strategic foresight is that the future is inherently unknowable, and efforts to get it exactly right are futile, our role as consultant and facilitator is to offer an expansion of the range and depth of possibilities for the organisation to consider, thereby reducing the likelihood and magnitude of surprise. The principal means of challenging the official future, one favoured by Hillbreak, is to develop alternative futures in the form of “Scenarios”.

Scenarios are instruments for ordering people’s perceptions about alternative future environments in which today’s decisions might play out. Scenario planning is now widely regarded as a basic tool for thinking strategically about the future. And scenarios have long been used by government planners, corporate strategists and military analysts as powerful aids in decision-making in the face of uncertainty. In practice, scenarios resemble a set of stories — possible, plausible, probable and preferable — built around carefully constructed plots. Such stories can express multiple perspectives on complex events, with the scenarios themselves giving meaning to these events.

The process is highly interactive, intense and imaginative. It begins by isolating the decision to be made, rigorously challenging the mental maps that shape people’s perceptions, and hunting and gathering information, often from unorthodox sources. The next steps are more analytical: identifying the driving forces, the predetermined elements and the critical uncertainties. These factors are then prioritised according to importance and uncertainty. Subsequently, three or four thoughtfully composed scenario “plots” are constructed, each representing credible alternative futures, against which policy options can be tested and implications identified.

Scenarios are powerful planning tools because the future is unpredictable. Their main characteristics being:

Good scenarios are conceivable and surprising. They have the power to break old stereotypes; and, by rehearsing tomorrow’s future, they produce better decisions today.

Example Scenarios developed by Hillbreak for a Strategic Foresight workshop for a leading global fund manager

Scenario logics are the basic building blocks from which the final scenarios will eventually evolve. Establishing them correctly, therefore, lays the foundations for the scenarios and is a vital prerequisite of good scenario planning as it:

The most common method is to construct a cross-matrix formed by selecting the two most critical pivotal uncertainties which might play the most prominent roles in shaping the future for the organisation concerned. Selecting the pair of pivotal uncertainties can involve long debates between participants in the exercise, but if the group wants to create coherent, creative scenarios then a reasoned explanation of the rationale behind the selection can itself be richly rewarding.

There is no ‘correct’ way to flesh-out the scenarios, but there are a number of important guidelines that can be followed regarding ‘factors’ and ‘actors’.

With regard to ‘factors’ there should be:

In respect of ‘actors’ they should represent:

The scenarios should be fleshed-out and exaggerated in opposite directions to create images of future worlds that are as different from each other as possible. The best scenarios are not only compellingly believable, but also present distinct alternatives, are internally self-consistent, vividly memorable, individually challenging, and sufficiently insightful and powerful enough for decision-making purposes.

Change occurs on many levels. Most organisations, short on time and beset with operational issues, spend insufficient time examining and understanding the deeper levels of change. This can be done by taking a ‘layered approach’, both ‘horizontally’ and ‘vertically’.

Horizontally, trends and drivers can be organised into areas or sectors by means of “STEEP” analysis (Social, Technological, Economic, Environmental, and Political) as explained in Part 2 of this blog series. Time-scales can also be examined horizontally by means of the “Three Horizons Method”, which, at Hillbreak, we apportion as “Evolutionary” (business developing as usual),”Transitional” (surveying emerging innovation and responding to present shortcomings) and “Transformative” (future systems of living, working, developing, operating and investing).

Vertically, a method known as “Causal Layered Analysis” (CLA) is employed to enable comparison of vertical ‘slices’ of reality and change. Popularly, most exponents of CLA identify four layers: surface/litany; social causes/systems; discourse/world view; and, metaphor/myth. At Hillbreak, we have devised a simpler version: Exploratory; Interpretive; and Empirical.

Layered approaches are important because organisations often become too narrowly focused on immediate problems, neglecting a broader and deeper exploration and understanding of the environment in which they operate. By adopting them, an organisation might realise that it has been focused on the wrong things, identify profound issues and changes that will impact upon it, and prompt the organisation to develop the necessary foresight to address those deeper drivers of change early enough to influence the outcomes — rather than just reacting to them after the event.

Most organisations have used scenario analysis to examine the likely development of core risk factors over time. An approach that can work well in an era of gradual change. At times like the present, however, it is extreme risks, (especially the “unknown unknowns”), not the everyday ones, that most concern some organisations in such fields as finance, energy and health. More recently, therefore, a new form of scenario planning has emerged — “Stress Testing” — to tackle the prospect of chaotic and immediate change. At Hillbreak, we recommend to clients operating in fields within international financial frameworks that stress-testing should be an element within their risk-management system. Notably, the recently published Recommendations of the Financial Stability Board Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures position scenario analysis and stress-testing as a central feature of decision-useful financial reporting in relation to climate change impacts. Performed properly and more widely, it can be a valuable tool in building the resilience that today’s business environment demands across myriad trends and uncertainties.

Thus, scenario planning, in all its manifestations, can: help explore and identify future possibilities; make people aware of risk and uncertainties; stretch the imagination; trigger the learning process; promote people’s participation in long-term decision-making and planning; and, evaluate current choices regarding the future. Nevertheless, always remember that you are NOT predicting the future but are trying to imagine it.

In this second article in our six-part series on Conducting Corporate Foresight, we focus on the Scanning the Horizon phase, which follows on from having established the Strategic Question that the Foresight process seeks to answer.

A prerequisite of all serious strategic policy studies is “Horizon Scanning”, alternatively known as environmental scanning. This stage in the Corporate Foresight process is not about making predictions, or even forecasts, but is a systematic exploration and investigation of evidence and ideas about future issues and trends. Sometimes it is described as creating a ‘systems map’ of the activity or organisation under consideration; but we prefer to add the power of ‘radar’ to this simile. Profound change invariably starts as a ‘blip’ or ‘weak signal’ on the periphery, and companies in complex, rapidly changing environments require well-developed peripheral vision and an alert sense of anticipation.

Effective horizon scanning needs structure. Probably the most familiar framework for searching the external contextual system for emerging trends surrounding an issue or organisation is “STEEP”, an acronym which we have modified to mean:

Essentially, STEEP allows for a broad examination of the environment, identifies the major forces of change and detects signals that might drive, disrupt or deflect them.

Alongside the STEEP taxonomy, at Hillbreak, we employ a “Three Horizons” framework which gives a richer meaning to the more traditional ‘short-medium-long’ term thinking commonly adopted:

More of an exploratory perspective than a planning tool, the Three Horizons technique can be used as a second axis with STEEP in providing a fuller framework for researching and recording potential change over time. Metrics can also be applied, where appropriate, to the drivers and issues involved. Such scanning has been sophisticated over recent years with the rise in knowledge management software, but we would still verge on the qualitative rather than the quantitative side of consultancy practice at this stage in the corporate foresight process.

Just over a decade ago, a revelatory survey of 140 corporate strategists, showed that fully two-thirds of respondents had been surprised by as many as three high-impact competitive events in the previous five years, and a shocking 97% said that their companies lacked an early-warning system. Little, we would argue, has changed since then, as subsequent happenings have surely demonstrated.

Horizon Scanning should be a permanent, structured and continuous process, embedded into the policy and planning procedures of any organisation. In doing so, and in addition to framing the right question, we would suggest the following practical guidelines:

Organisations with a constant horizon scanning capacity and strong peripheral vision will always gain significant advantage over their rivals. They will recognise risk more readily and reorganise accordingly. They will perceive and act on opportunity smartly and in front. As the business environment changes apace and becomes more uncertain, payoffs from scanning and vision will be greater than ever. As Charles Darwin popularly pronounced:

“It’s not the strongest of the species who survive, nor the most intelligent, but the ones most responsive to change.”

It might seem an overused assertion, but leadership in the corporate realm faces new uncertainties greater than at any time before. The global pace of change, and the ramifications of it, seriously tests the capacities of businesses, of all scales and sectors, to formulate and implement resilient plans and adaptive strategies.

It is why, at Hillbreak, we advocate frequently the adoption of ‘Strategic Foresight’ by our clients, whether as a feature of developing or refreshing Responsible Investment strategies, or as part of business planning processes more broadly. The concept, and the six-stage approach that we adopt, is one that we have summarised in a previous introductory article.

This post, the beginning of a new, monthly series that will provide greater depth on the six stages in the Strategic Foresight process, focuses on the first: Framing the Strategic Question.

All too often insufficient time and thought is given at the outset of a project to defining the scope and focus of the issues facing an organisation. Not infrequently, studies end-up addressing the wrong problem or discovering the real issue halfway through having generated considerable confusion along the way. It is therefore not simply a matter of asking the right question, but of framing it within the context and purpose of the organisation. To achieve this, we have a few key guidelines, as follows:

No two organisations are alike; what works well with one might easily backfire with another. Central to our process is an opening series of tailored ‘strategic conversations’ with selected players from within and, where appropriate, outside the organisation.

We also favour the familiar, yet forever fruitful, Strengths-Weaknesses-Opportunities-Threats (SWOT) analysis. But it is important not to over-sophisticate the process; large measures of common sense are critical.

Getting all client stakeholders to buy-in to the strategic foresight process is not always easy. Internal participants can be sceptical and may perceive that the foresight consultant is not paying sufficient attention to the immediate concerns of the financial bottom-line. Time spent explaining the rationale and the method is, therefore, never wasted.

Neither is crafting a positive depiction of the future and exploring the biases of both the participating client groups and the facilitator. Too many foresight exercises concentrate narrowly on highlighting hazards and negative impacts. Of course, researching and evaluating risks is crucial, but it is only one side of the futures coin.

Primarily, foresight requires the ability to recognise patterns involving relationships and systems that are complex and non-linear. This often entails a significant realignment of mind-sets among participants.

The essential purpose of employing futures-thinking and foresight methodology is to gain a better understanding of the opportunities and challenges that lie ahead, so that superior decisions can be taken today. Fundamentally, therefore, the client organisation must resolve what it wants to achieve. This is not as simple as it sounds. Aspirations and perceptions vary considerably over corporate time-horizons and across business imperatives.

Firms can be quite unclear as to what decisions they need to make to secure their future. Investing time and effort up-front clarifying the focal objectives, motivations and reasoning pays enormous dividends. In our experience, a prime outcome of foresighting is getting client companies to balance successfully the exploitation of the near-term (day-to-day operational management) with an exploration of the longer-term (blue-sky strategizing). The two, ideally, should feed off each other.

Defining the purpose of the strategic foresight project and the related objectives of the organisation is imperative. Some of these might be quite specific, addressing a known issue (e.g. merger, relocation, new product development, re-organisation etc.); others more ethereal (e.g. creativity, innovation, corporate citizenship, responsible investment, well-being or enlightened leadership etc.).

Generally, the overriding objective is to bring fresh thinking, new ideas and a change of mind-set into organisations all too often stuck in self-constructed ‘silos’ of planning and operation. An effective foresight project should help a client focus on ‘outcomes’ not ‘outputs’ and work across multiple time-horizons.

It is essential that the support of the Executive is in place. That said, strategic foresight is a ‘team sport’. From experience, the core group driving the project should be no greater in number than five or six, whilst strategic conversations should be conducted with around a dozen or so carefully chosen ‘players’. It is often preferable for this to include a few well-informed, external stakeholders.

Strategic foresight workshops should comprise anything from 12 to 30 participants who are truly representative of the organisation. They should ideally be complemented by some provocateurs who can offer differing views of the organisation and the world at large.

It is important to recognise throughout that strategic foresight requires creative, collaborative and challenging thinking. The ultimate message might best be formed in a favourable light so that recommendations are evaluated positively, but we do not exist to tell organisations what they want to hear. In our experience, clients today place far more value on candour and integrity.

In this latest post, Professor John Ratcliffe, newly appointed Head of Strategic Foresight at Hillbreak, introduces the concept and corporate benefits of the discipline.

Leading an organisation through these turbulent times of market, technological and geo-political uncertainty is a major challenge. The risks attached to changing investment conditions and the ambiguity of professional pundits make it difficult for decision-makers to look ahead to the future and to frame the destiny of their organisation within it.

Yet the future is not predestined; we can shape and manipulate it if we know what we want it to be. Nor can the future be predicted. It can be explored and examined imaginatively though; challenging conventional assumptions, preparing for inevitable surprises and envisioning a range of scenarios from which to plan backwards.

This approach to viewing what can be done today – whether by organisations, individuals, cities or communities – to positively influence the future is known as “Strategic Foresight”.

At Hillbreak, we take a common-sense approach to Strategic Foresight comprising a six-stage formula.

Frequently, our last question to the client is: “What are you going to do first, and now?”

Apart from the goals of capturing materiality, producing a strategic plan to guide organisations into the future, and giving their stakeholders confidence in their ability to adapt and manage risk, we find that the simple act of getting people together to share a common interest to think, talk, plan and act – creatively and differently – is exhilarating and corporately fruitful.

At Hillbreak we provide strategic consultancy services to organisations seeking competitive advantage in a changing urban world. This ranges from extensive professional studies of client organisations – challenging where they are going, what they are going to do, and how they are going to get there – to workshops and symposia for companies and their stakeholder networks.

“We do not need magic to transform our world. We carry all the power we need inside ourselves already. We have the power to imagine better.” J.K. Rowling, Harvard, 2008.

This site uses cookies. You can choose whether or not to accept them here. View settings for specific details about the cookies we use.

Accept all CookiesNo ThanksSettingsWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them:

You can read about our cookies and privacy settings in detail on our Privacy Policy Page.

Privacy Statement