Strategic Foresight: Stage 3 – Forecasting Alternative Scenarios

Forecasting Alternative Scenarios

Essentially, forecasting involves generating the widest range of creative possibilities, then consolidating and prioritising the most useful for an organisation to consider and prepare for as it moves ahead. Appreciating that a key tenet of strategic foresight is that the future is inherently unknowable, and efforts to get it exactly right are futile, our role as consultant and facilitator is to offer an expansion of the range and depth of possibilities for the organisation to consider, thereby reducing the likelihood and magnitude of surprise. The principal means of challenging the official future, one favoured by Hillbreak, is to develop alternative futures in the form of “Scenarios”.

What Are Scenarios?

Scenarios are instruments for ordering people’s perceptions about alternative future environments in which today’s decisions might play out. Scenario planning is now widely regarded as a basic tool for thinking strategically about the future. And scenarios have long been used by government planners, corporate strategists and military analysts as powerful aids in decision-making in the face of uncertainty. In practice, scenarios resemble a set of stories — possible, plausible, probable and preferable — built around carefully constructed plots. Such stories can express multiple perspectives on complex events, with the scenarios themselves giving meaning to these events.

How Do You Create Scenarios?

The process is highly interactive, intense and imaginative. It begins by isolating the decision to be made, rigorously challenging the mental maps that shape people’s perceptions, and hunting and gathering information, often from unorthodox sources. The next steps are more analytical: identifying the driving forces, the predetermined elements and the critical uncertainties. These factors are then prioritised according to importance and uncertainty. Subsequently, three or four thoughtfully composed scenario “plots” are constructed, each representing credible alternative futures, against which policy options can be tested and implications identified.

Why Use Scenarios?

Scenarios are powerful planning tools because the future is unpredictable. Their main characteristics being:

- Scenarios present alternative images instead of extrapolating trends from the present.

- Scenarios embrace qualitative perspectives as well as quantitative data.

- Scenarios allow for sharp discontinuities to be evaluated.

- Scenarios require decision-makers to question their basic assumptions.

- Scenarios create a learning organisation possessing a common vocabulary and an effective basis for communicating complex – sometimes paradoxical – conditions and options.

Good scenarios are conceivable and surprising. They have the power to break old stereotypes; and, by rehearsing tomorrow’s future, they produce better decisions today.

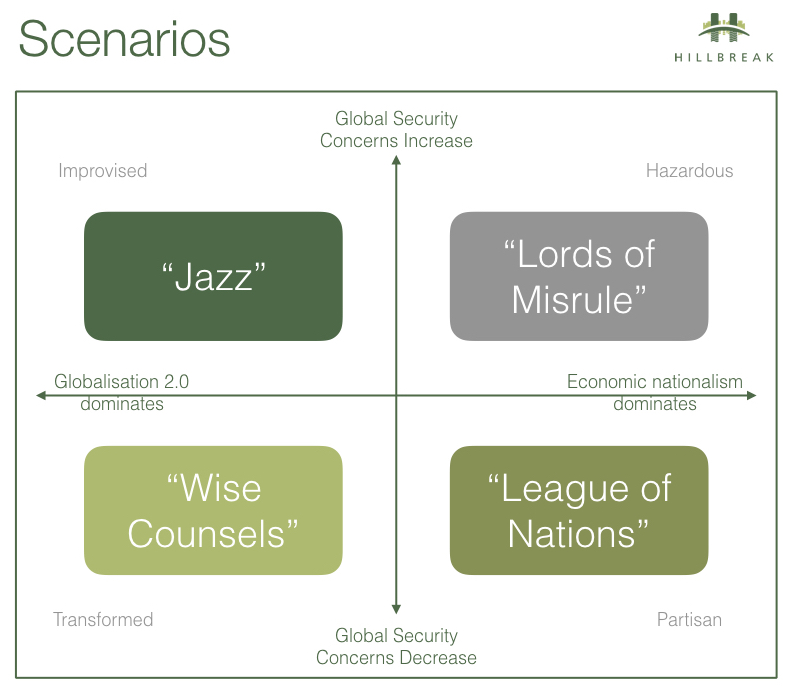

Example Scenarios developed by Hillbreak for a Strategic Foresight workshop for a leading global fund manager

How to Establish Scenario Logics

Scenario logics are the basic building blocks from which the final scenarios will eventually evolve. Establishing them correctly, therefore, lays the foundations for the scenarios and is a vital prerequisite of good scenario planning as it:

- produces the logical rationale and framework for the scenarios;

- determines the underlying theme, structure and background of each scenario;

- establishes the plot of each; and,

- captures the dynamics of the situation in each scenario, so that they can be communicated effectively.

The most common method is to construct a cross-matrix formed by selecting the two most critical pivotal uncertainties which might play the most prominent roles in shaping the future for the organisation concerned. Selecting the pair of pivotal uncertainties can involve long debates between participants in the exercise, but if the group wants to create coherent, creative scenarios then a reasoned explanation of the rationale behind the selection can itself be richly rewarding.

Fleshing-out the Scenarios

There is no ‘correct’ way to flesh-out the scenarios, but there are a number of important guidelines that can be followed regarding ‘factors’ and ‘actors’.

With regard to ‘factors’ there should be:

- a beginning, a middle and an end state;

- an approximate time-line;

- key events that make things happen;

- early indicators of change (signals that the scenario is unfolding); and,

- an evocative title.

In respect of ‘actors’ they should represent:

- main players in the field of interest;

- large, small and traditional stakeholders;

- new entrants;

- what regulators are doing; and,

- what society is demanding.

The scenarios should be fleshed-out and exaggerated in opposite directions to create images of future worlds that are as different from each other as possible. The best scenarios are not only compellingly believable, but also present distinct alternatives, are internally self-consistent, vividly memorable, individually challenging, and sufficiently insightful and powerful enough for decision-making purposes.

A Layered Approach

Change occurs on many levels. Most organisations, short on time and beset with operational issues, spend insufficient time examining and understanding the deeper levels of change. This can be done by taking a ‘layered approach’, both ‘horizontally’ and ‘vertically’.

Horizontally, trends and drivers can be organised into areas or sectors by means of “STEEP” analysis (Social, Technological, Economic, Environmental, and Political) as explained in Part 2 of this blog series. Time-scales can also be examined horizontally by means of the “Three Horizons Method”, which, at Hillbreak, we apportion as “Evolutionary” (business developing as usual),”Transitional” (surveying emerging innovation and responding to present shortcomings) and “Transformative” (future systems of living, working, developing, operating and investing).

Vertically, a method known as “Causal Layered Analysis” (CLA) is employed to enable comparison of vertical ‘slices’ of reality and change. Popularly, most exponents of CLA identify four layers: surface/litany; social causes/systems; discourse/world view; and, metaphor/myth. At Hillbreak, we have devised a simpler version: Exploratory; Interpretive; and Empirical.

Layered approaches are important because organisations often become too narrowly focused on immediate problems, neglecting a broader and deeper exploration and understanding of the environment in which they operate. By adopting them, an organisation might realise that it has been focused on the wrong things, identify profound issues and changes that will impact upon it, and prompt the organisation to develop the necessary foresight to address those deeper drivers of change early enough to influence the outcomes — rather than just reacting to them after the event.

Stress Testing

Most organisations have used scenario analysis to examine the likely development of core risk factors over time. An approach that can work well in an era of gradual change. At times like the present, however, it is extreme risks, (especially the “unknown unknowns”), not the everyday ones, that most concern some organisations in such fields as finance, energy and health. More recently, therefore, a new form of scenario planning has emerged — “Stress Testing” — to tackle the prospect of chaotic and immediate change. At Hillbreak, we recommend to clients operating in fields within international financial frameworks that stress-testing should be an element within their risk-management system. Notably, the recently published Recommendations of the Financial Stability Board Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures position scenario analysis and stress-testing as a central feature of decision-useful financial reporting in relation to climate change impacts. Performed properly and more widely, it can be a valuable tool in building the resilience that today’s business environment demands across myriad trends and uncertainties.

Conclusion

Thus, scenario planning, in all its manifestations, can: help explore and identify future possibilities; make people aware of risk and uncertainties; stretch the imagination; trigger the learning process; promote people’s participation in long-term decision-making and planning; and, evaluate current choices regarding the future. Nevertheless, always remember that you are NOT predicting the future but are trying to imagine it.