IMPACT FINANCE SERIES: Part IV – The Future

In this series, we’ve explained the characteristics and definitions of different investment styles and themes, explored their emergence and growth across the capital markets, and examples of their deployment in the real estate sector. To finish the series, we turn our attention to what might be expected going forward, including with respect to transforming capital allocations, developing governance, oversight and transparency, and accelerating product innovation. There’s a very clear message for investors and intermediaries to conclude.

From niche to universal

Regulators and investors alike are increasingly signing up to the theory that for investments to be considered well managed, they must manage all the relevant risks, including environmental and social factors. For this to be done, these risks must be both well-articulated (and thanks to the likes of TCFD, the EU, the UN and the GIIN this is increasingly so) and well-priced.

This means that it is inevitable that measurement of the sustainability and impact of investments will apply to all, and not just those emerging products which were once considered niche.

Thanks to the emerging regulation and market consensus around the definitions, investors can now begin to look again at their portfolios and determine which of their investments are:

- Good enough – genuinely sustainable, meaning doing no harm and adequately addressing specific environmental and social risks;

- Improving – having a measurable, positive impact in terms of reducing, managing or mitigating environmental and social risk. Note that these two categories are not mutually exclusive; or

- Not good enough / unknown – either having a negative impact, or unable to articulate and measure their impact and therefore not able to adequately manage or mitigate environmental and social risks.

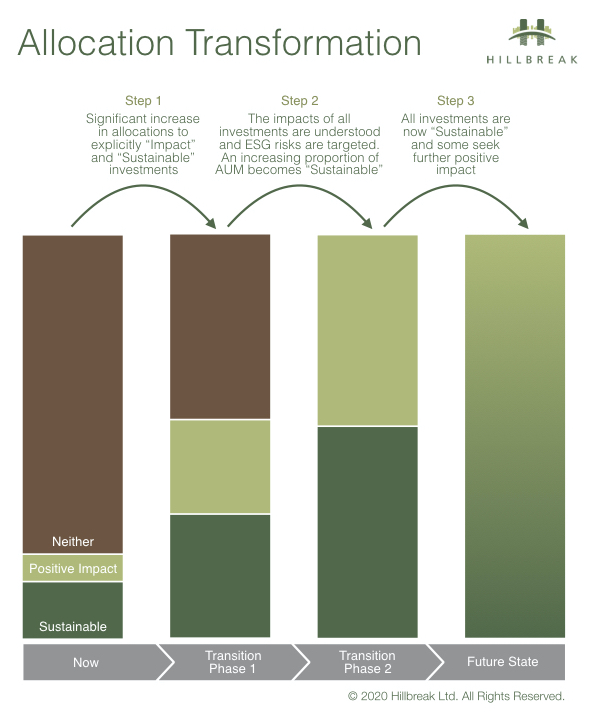

The journey all responsible investors must go on should involve a transformation of their allocations using these lenses, as shown below.

Governance and oversight

The evolution of the governance and oversight of investments is already underway. Regulators have been highlighting the extent to which banks and insurers are exposed to environmental risk[1], and have begun stress testing for this risk. In order to assess capital adequacy, this means both the financiers and the regulators must be able to identify and price the risk.

In the pensions arena, trustees face new legal duties to disclose how they deal with stewardship and financially material ESG matters. The UK’s Pensions Regulator has said climate change is a core financial risk that trustees will need to consider when setting investment strategy. Therefore, this means that UK pension funds will be increasingly aligned with their Northern European and Australian counterparts, who have long-since seen good management of environmental, social and governance risk as a prerequisite to any allocation or capital to an investment intermediary[2].

Trustees are duty-bound to consider the financial implications of their decisions, which includes the financial risk associated with climate change, and presumably the financial risks associated with social and governance issues. Beyond the requirement to consider and disclose how they deal with these issues, pension trustees in England now also have case law to consider[3]. According to legal firm Charles Russell[4], pension trustees may also potentially take into account non-financial issues if:

- the trustees have good reason to think that the scheme members hold the relevant concern; and

- the decision does not involve significant financial detriment.

Measurement, Reporting and Verification

In order to properly take the financial implications of these issues into account, and to reflect the wishes of their members with regard to the non-financial implications, investors will need reliable measurements for both.

There can be no doubt that there has been a dizzying array of certifications and methodologies, which can be baffling for the well-meaning investor or asset owner, so much so that a not-so-mini-industry in advice and compliance support has emerged[5] [6], including specifically within the real estate sector where a growing number of multi-disciplinary and boutique firms compete for data management, reporting and verification mandates.

In the real assets investment world – which we should remember is underpinned by increasingly globalised capital flows – voluntary certifications and standards abound for assets, portfolios and organisations. They include myriad competing and overlapping rating and certification systems, standards, benchmarks and indices. Some of these are particular to local markets, but many compete in an international context. Backing the right horse, each of which has its own inherent bias, can be a significant challenge for asset owners and managers alike, which is a key reason behind the decision of many to use multiple systems for the same purpose, often at considerable cost.

These systems have no doubt served an important purpose, and will continue to be used in the medium term, but many may require significant revision once regulatory standards (such as those in train in the EU), and accounting standards (such as those put forward by the Sustainable Accounting Standards Board)[7] come into widespread usage.

In the same way that investors and analysts can rely upon audited financial statements and regulated reporting of financial performance, similar levels of trust must be built into the reporting and verification of environmental and social performance. If companies and intermediaries want to access the wall of capital represented by the TCFD, which now has the support of over 1,000 organisations[8] controlling balance sheets totalling $120 trillion[9], or the Climate Action 100+ which represents some of the world’s largest pension funds with over $40trn in assets[10], then they must report independently verified ESG performance. Otherwise they may find themselves capital starved as the market moves forward.

There can be no doubt that a global approach is required, increasing common understanding across different products, sectors and across the ESG issues[11]. The result must be to facilitate and direct the flow of capital, not to confound it.

Comparison

The emerging consistency in approach to labelling of products and measurement of environmental and social risk management introduces for the first time the possibility of widespread direct product and manager comparison. Investors and consultants will be able to see which intermediaries and investee companies are able to manage environmental and social risk well, alongside financial risks. It will become clear who can deliver and who can’t. Capital allocations will follow.

Comparison of relative performance of risk managers will become even easier as the EU introduces its new ‘PACT’ benchmark standards – introducing clear standards for benchmarks to compare the performance of ‘Paris Aligned’ and ‘Climate Transition’ investments. Intermediaries who are marketing environmentally-focused sustainable and impact products will inevitably be compared to these new benchmark standards, and their strategies will be compared not only to those of other managers, or to ‘brown’ investments, but also in terms of their alignment to the 1.5 degree pathway (PA) and the 2 degree pathway (CT). The recently launched Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM)[12], funded under the EU’s Horizon 2020 programme with additional support from investment institutions including APG, PGGM and Norges Bank Investment Management, is a notable example of a tool intended for precisely this purpose, helping asset owners identify and quantify stranded asset risk.

Issuers of real assets and alternative investment products which are seeking to ride the growing wave of capital seeking sustainability and impact would do well to ensure their products meet the requirement for inclusion in these benchmarks, and indices which will no doubt develop around them. These will soon become a very easy route for capital allocators.

Product innovation

Rating Agencies

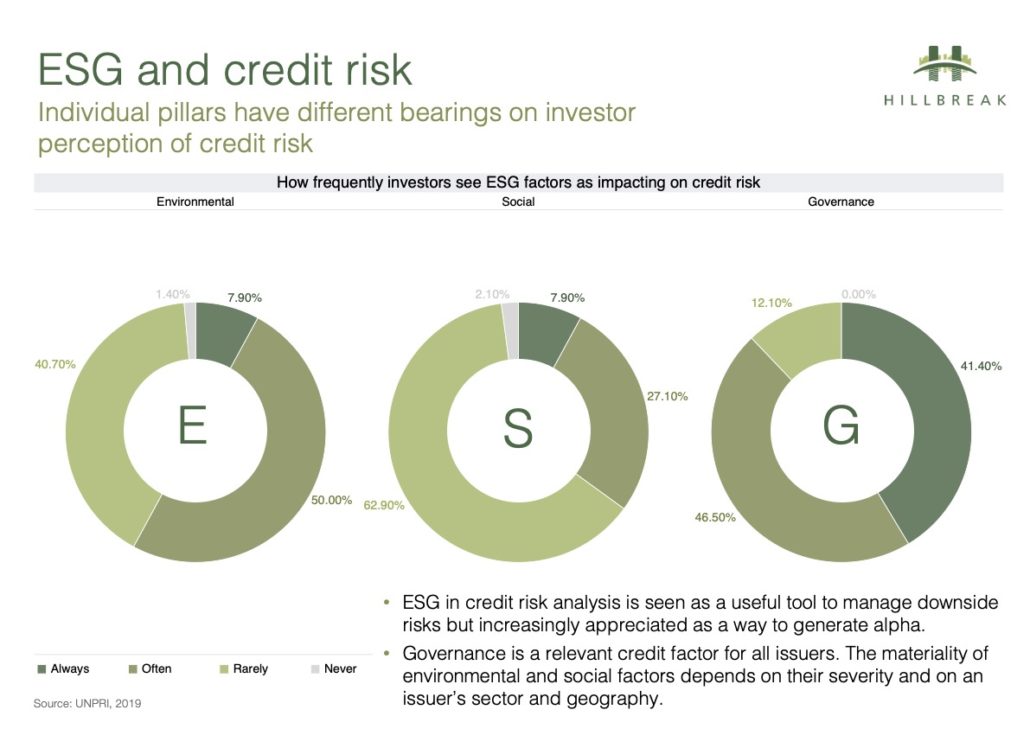

UNPRI has shown that ESG factors are relevant to investors’ view of credit risk, but ratings agencies still tend to look at ESG as a separate issue, even providing separate ESG rating services[13] [14] [15]. In future we should expect that these risks are seen as integral to all economic activity and, therefore, they should also be integrated into all credit ratings.

ESG in credit risk analysis is seen as a useful tool to manage downside risks but increasingly appreciated as a way to generate alpha. Governance is a relevant credit factor for all issuers. The materiality of environmental and social factors depends on their severity and on an issuer’s sector and geography.

Lending

In the second article in this series we learned about the RCF used by GPE to finance environmental improvements to its portfolio, judged against 3 environmental KPIs. If these are met, the rate on the loan will drop by 2.5 basis points, and GPE will give the difference to charity. If they are not met, then the lenders’ rate will remain the same and GPE will still make the donation. This is a clear acknowledgement by the lenders that management of ESG risk is fundamental to credit risk, and therefore a reduction in this risk can be tied to a reduction in the rate they demand for their lending.

This innovation could go further. KPIs are not traditional loan covenants which would cause the bank to step in, perhaps to renegotiate their rate, call in the loan, take security over assets or demand remedial action by management. Banks do have both operational covenants, such as requiring borrowers to file their accounts and pay their taxes on time, and maintain adequate insurance. Banks could request covenants related to maintaining or improving ESG performance.

If penalties for breach of ESG covenants led to financial penalties for borrowers, then it could potentially frustrate the original intended “use of funds”. But the same is true of all project finance, and in that market banks are not afraid to use milestones and covenants to manage the risk which they take on. It seems there is room for the lenders to go further in sustainable and impact lending, and this would be welcomed by shareholders. Thanks to shareholder activism, Lloyds has committed to halving the carbon emissions related to its loan book, and Barclays has come under pressure to phase out all lending to fossil fuel companies[16].

Securitisation

In Part II of this series, we learned that Generali has developed a framework for green insurance linked securities [17] which would see both the freed-up capital and proceeds of ILS being used for further ‘green’ investment. Banks could add these concepts to their ‘green bonds’ – thereby expanding the additionality and impact of the securities they issue, rather than simply passing on their already ‘green enough’ assets. Likewise, this concept could be expanded to social impact bonds.

Collaboration – across debt, equity and insurance

Since banks and borrowers are increasingly looking to price ESG risk into the pricing of debt facilities, the cost of failing to meet ESG covenants or KPIs will be more visible. Borrowers’ ability to meet these KPIs will also be impacted by climate change, for example demand for heating and cooling going up as weather becomes more extreme. One can see that the weather hedging products which the insurance and reinsurance industry regularly provide could help borrowers to isolate the ESG risk which they control, and “back out” the risk that they don’t. This could even allow borrowers and lenders to agree more challenging covenants.

Weather hedging products traditionally used in the agriculture and construction sectors to manage the risk of crop failure or delays in completion and are now being used to help de-risk the project financing and ongoing financial performance of renewables. There could be space for further innovation here, with insurers following the banks’ lead and giving preferential pricing for sustainable or impact weather cover. For example, covering the weather and climate risk on the construction of sustainable assets in real estate, social and economic infrastructure.

The Sierra Re catastrophe bond which completed in January 2020 was the first parametric catastrophe bond to cover earthquake risks embedded within a portfolio of mortgage investments[18]. This concept could be incredibly helpful to lenders and investors alike, allowing them to price and manage ESG risks across their portfolio.

The next 5 years

The world of sustainable and impact investment is developing apace. Those intermediaries which understand the direction of travel for the regulation of environmental and social risk management, and the redirection of capital which will follow, stand to gain a great deal. Those who fall behind will find themselves with decreasing prices in increasingly illiquid assets.

[1] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/publication/2019/enhancing-banks-and-insurers-approaches-to-managing-the-financial-risks-from-climate-change-ss[2] https://www.ipe.com/pensions/country-reports/uk/uk-esg-moves-up-the-trustee-agenda/10032972.article

[3] https://www.ftadviser.com/pensions/2020/01/10/landmark-vegan-case-threatens-to-disrupt-pensions-industry/

[4] https://www.charlesrussellspeechlys.com/en/news-and-insights/insights/employment-pensions-and-immigration/2020/saving-the-world–investing-for-a-cause—can-pension-trustees-do-so/

[5] https://www.afire.org/esg-without-certification-is-it-possible-what-does-that-look-like/

[6] https://www.reinventinggreenbuilding.com/the-book

[8] https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/PR-TCFD-1000-Supporters_FINAL.pdf

[9] https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019-TCFD-Status-Report-FINAL-053119.pdf

[10] https://climateaction100.wordpress.com/about-us/

[11] https://www.environmental-finance.com/content/analysis/the-ifcs-principled-approach-to-impact.html

[12] https://www.crrem.eu/tool/

[13] https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/products-benefits/products/esg-evaluation

[15] https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20190107005524/en/Fitch-Ratings-Launches-ESG-Relevance-Scores-Show

[16] FT – Lloyds vows to halve emissions linked to its loan book

[17] https://www.artemis.bm/news/generali-develops-framework-for-green-insurance-linked-securities-ils/

[18] https://www.artemis.bm/news/recent-parametric-cat-bond-a-really-important-transaction-swiss-re-ceo-explains/

The amount of

The amount of